Carbon capture for a productive and sustainable Europe

“The science is clear. Industrial carbon removal is a necessary part of our climate toolbox”

Ursula von der Leyen, European Commission President

“There is, my friends, no chance in hell that we will meet the global climate targets without CO2 storage”

Lars Aagaard, Danish Minister for Climate, Energy and Utilities

Strong and wise words at the recent launch of the the Greensand project, a pioneering offshore carbon storage site just launched in the North Sea. This endorsement of carbon capture and storage (CCS) echoed the announcement of the European Commission’s Net-Zero Industry Act, (NZIA) which sets the objective of an annual 50Mt storage injection capacity in the EU by 2030, requiring contributions from EU oil and gas producers. Although we understand we needed to start somewhere, this mandate on our companies is not great news and, while a commendable objective, certainly not the best way to regulate. Such an objective will be challenging for our industry to achieve within the timeframe, as the projects depend on factors partially outside the control of the obligated companies.

A recognised and proven technology that now needs a value chain

CCS promoters have long said the technology was crucial for the future of industry in Europe, to keep it globally competitive, compatible with climate neutrality, and to safeguard the jobs, research and innovation associated with it. For decades, their calls found little favor within EU policymaking circles. The lack of an economic case for the technology prevented project development in Europe.

The NZIA’s recognition of the role of CCS as a key enabler of sustainable competitiveness for industry in the EU is a welcome and overdue development, as is the possibility for CO2 storage projects to be recognized by Member States as ‘net-zero strategic projects’. Our sector is ready to work with EU institutions and national authorities to establish the needed measures and framework so that CCS deployment actually takes off and meets (and potentially exceeds) the ambition laid down by the Commission.

A wind of change

While factors such as the increasing costs of EU carbon permits (reaching a high of €100 in February), the reduction of free allowances for industry, and the idea of European strategic autonomy (reinforced by the recent deployment of the Inflation Reduction Act in the US) help the commercial case for CCS, more funding and de-risking measures are needed to establish complex value chains from emitters to storage sites.

After years of inaction and doubt, there now seems to be general consensus in Europe on the need to come together and drive CCS deployment. The European Commission was among the first to act and launch a much-needed EU CCUS Forum in 2021, bringing together all value chain actors, academics and civil society to work on identifying and lifting barriers and accelerating deployment. a

In early 2023, the Net Zero Industry Act took the discussion to the political level, proposing an EU ambition for 2030, to drive deployment and mobilize actors across the continent. Even Germany, a country long sceptical about CCUS, signed a declaration of intent with Denmark which acknowledges the technology’s role in the fulfilment of national climate goals and recognizes the ‘importance of science in the promotion and development of CCUS’. Finally…

The EU and Member States need to turn this newfound political momentum into urgent action on the ground, because while this is an extremely positive development, the window for action is very short: the EU has some months to get its regulatory framework in shape if it wants to achieve its 2030 CCUS ambition: important work on defining the requirements still needs to be undertaken

Making the business case

CCS is considered a crucial strategy for reducing emissions due to its significant potential. However, given the late attention it got, the prospect of large-scale commercialization of CCS in the near future is fraught, as it faces technical, economic, and social barriers that bring about uncertainties, impacting investment decisions. CCS developers still need government assistance to initiate projects due to the risks associated with the new will to develop this technology at scale, the absence of a well-established value chain and economic model, and the early stage of industry development.

Despite the Commission’s newfound enthusiasm, targets alone – and, in the NZIA’s case, obligations – aren’t sufficient to create a business case for CCS.

The EU and Member States need to put in place mechanisms to fund and de-risk the CCS value chain, such as contracts for difference. This mitigates the investment risk for companies and distributes the cost of CO2 between private and public entities.

Such contracts are especially pertinent for those contemplating investments in low-carbon technologies as they enhance the competitiveness of low-carbon solutions in the medium to long term. Further exploration of how the multiple possible funding sources for CCS project developers can be better streamlined is needed and the NZIA should simplify and accelerate the application process for funding.

Projects lighting the way

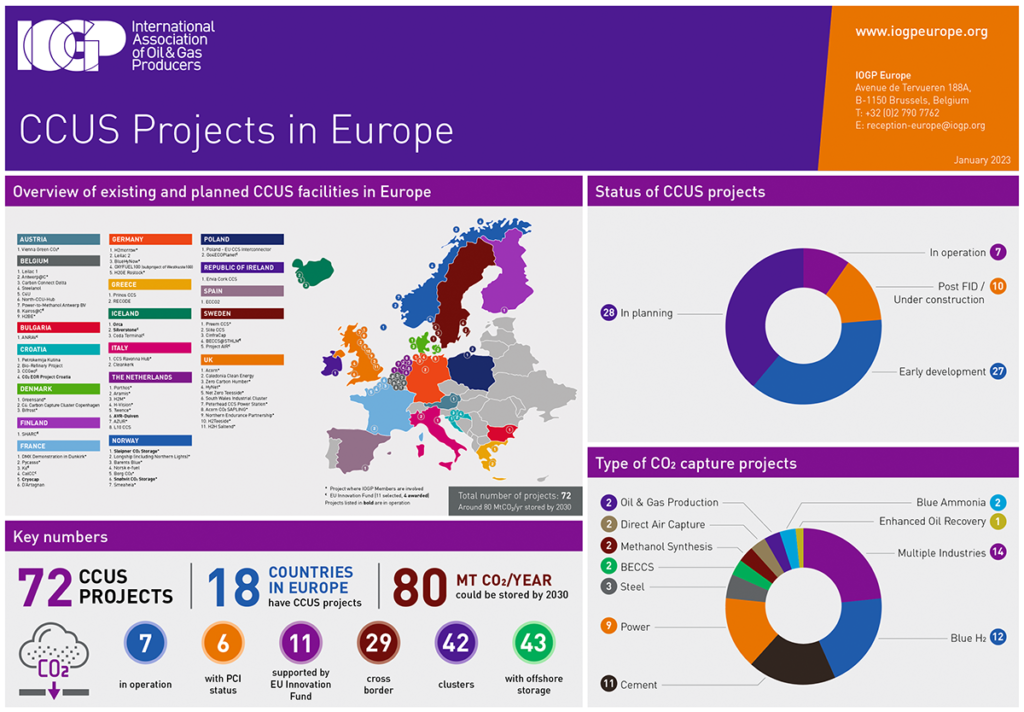

The NZIA targets a 50Mt injection capacity by 2030. CCS projects, both planned and underway across the Europe (EU, EEA and UK) foresee a capacity of an estimated 80Mt. Currently there are 30 storage projects in different stages of development in Europe. These projects are best developed around industrial clusters that share part of the infrastructure in the CO2 value chain, allowing significant reduction in development costs. The potential is there, but they will only take shape if there is a solid business case to underpin investments into projects. Individual Member States will also need to reconsider their positions on permitting CO2 storage sites. The chart below outlines existing and planned CCS projects across Europe. (https://iogpeurope.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/Map-of-EU-CCUS-Projects.pdf)

Scaling up Hydrogen

One of the most overlooked and yet main benefits of CCS technology is its potential to decarbonize natural gas and help produce very large amounts of low-carbon hydrogen relatively quickly. By capturing and storing the CO2 emitted during the steam methane or autothermal reforming process, low carbon hydrogen can achieve emissions reductions of up to 90% compared to traditional hydrogen production.

Not only would this accelerate the creation of a hydrogen economy by increasing the availability of volumes for consumers, but it would also provide an additional investment incentive for CCS. It’s a win-win for everyone, climate included.

So far, the EU seems determined to put nearly all its eggs in the renewable hydrogen basket – a very risky bet. This classic European ‘technology-specific’ approach is in stark contrast with the US approach to hydrogen deployment: public support available to all hydrogen production methods but proportional to the latter’s carbon intensity. A simple, climate-conscious and result-oriented approach. The speed and scale of investment in the US is telling.

But even if the EU persists in its current approach, the regulatory framework must be made much more inclusive and pragmatic than it currently is. At the moment, there are too many legal and administrative barriers to the introduction of hydrogen into the gas grid. It is important that regulatory efforts adopt a technology-neutral approach to scaling up hydrogen, ensuring all low-carbon technologies can fulfil their potential.

One of the main advantages of low carbon (or ‘blue’) hydrogen production is that it can re-use existing natural gas infrastructure which makes it an attractive option for countries with established natural gas industries.

In Europe, countries such as the Netherlands, Norway, and the UK have significant natural gas reserves and infrastructure, which makes them well-positioned to develop low carbon hydrogen production.

A recent study confirms European oil and gas pipelines’ ability to transport CO2 and hydrogen cost-efficiently.

The establishment of a competitive hydrogen market and cost-effective, cross-border hydrogen infrastructure is crucial for the widespread adoption of hydrogen production and consumption. Leveraging CCS to accelerate this process is a no-brainer.

The need for immediate action

Considering the targets proposed in the NZIA, the window to lift barriers and establish incentives is short – a couple of years at most. The EU needs to put its foot to the pedal on policy support for CCS. For CO2 to be effectively captured, transported, processed, and permanently stored, all entities along the value chain need to have viable and sustainable business cases with signed agreements underpinning investments and defining their locations, capacities, and timing.

It is also crucial to simplify and speed up the funding and state-aid processes in the EU. The Commission clearly tried to solve the ‘chicken and egg’ issue by proposing an obligation on the storage side to reassure industrial emitters. But investments in storage capacity development needs to be underpinned by signed agreements with emitters or aggregators, otherwise they will simply lead to expensive stranded assets. The European Commission and all legislative actors, including Member States, must unanimously encourage the development of CCS. It is crucial for avoiding offshoring our emissions, while reducing the risk of repatriating more of our industry, jobs, and much of the accompanying research, development and innovation. Possibly for good.

Europe’s industrial base, security and climate targets depend on it. We cannot miss it this time.