Micromobility “Made in Europe” to Achieve our Climate Targets and Make our Cities More Sustainable

Micromobility, in the form of e-scooters, e-bikes and other purpose-built vehicle for urban logistics, is a thriving market with the potential to create 1Mn jobs in the EU and to reduce emissions by 30MtCO2eq by 2030. This makes it one of the key drivers to transform and decarbonise the EU’s transport system. To seize this opportunity, the effort should go towards innovative micromobility solutions “Made in Europe”. To this end, the EU should adapt its policy and regulatory framework and support investments.

Mind the Gap ! How Micromobility Can Support the Decarbonisation of Transport

The decarbonisation of transport remains a major challenge in Europe’s endeavour to become the first climate-neutral continent. Domestic transport represents 23% of the EU’s GHG emissions and, contrary to other sectors, is trending upwards.1 Even with measures currently planned by the Member States, its emissions in 2030 are expected to remain above 1990 levels.

It is therefore critical to step up our efforts to meet the objective of the Sustainable and Smart Mobility Strategy to reduce emissions of the transport sector by 90% by 2050. To achieve this, road transport, which accounts alone for 20% of our GHG emissions, will need to reach net-0.

Green electrification for cars and vans is a no brainer. However, the uptake of electric vehicles is insufficient to tackle the projected increase in demand for mobility2.

In a recent study, McKinsey estimates that electrification will fall short of delivering 165 MtCO2eq emission reduction for transport to make a fair contribution to the 2030 target3. This gap could be addressed by reducing the kilometers travelled with ICE vehicles and accelerating the ICE park turnover: both can be achieved through modal shift i.e. replacing cars and vans by more climate-friendly solutions.

In cities, the need for sustainable mobility intersects with the need to increase the livability of urban life by reducing congestion, air pollution, noise, and land usage for streets and parking. Micromobility, comprising light electric vehicles like e-bikes, e-scooters, e-mopeds, as well as an increasingly rich offer of purpose-built vehicles, offers an ideal alternative. Indeed, the GHG emissions of 1 average ICE car is equal to that of 2 electric cars and of 7 to 12 e-scooters. The space needed for 1 car is roughly that needed for 12 e-scooters.

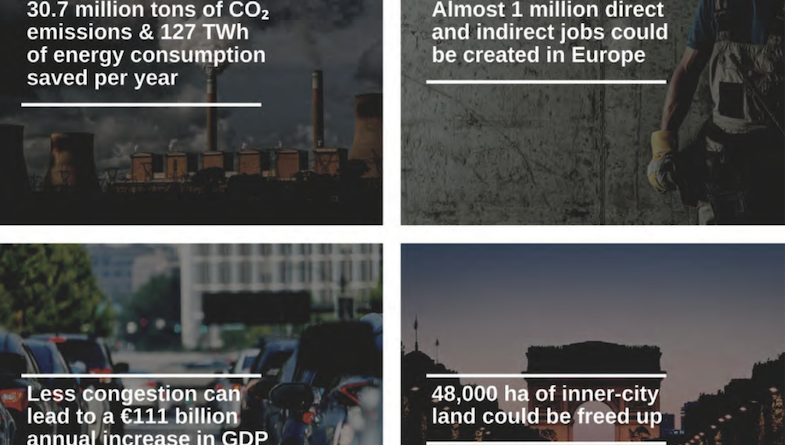

By switching from cars and vans to micromobility for about 10% of the trips less than 8km in just 100 large European cities, about 30MtCO2eq could be avoided, up to 130TWh of energy consumption could be saved, and up to 50.000 ha of inner-city land could be freed up.4

This represents abating about 6% of all GHG emissions from road transport, with immediate results, as the solutions are readily available.

Harvesting the Micromobility Economy with a Value-Chain “Made in Europe”

It is not a matter of whether micromobility will happen but rather how (and how fast). It is already largely present in our cities. However its anarchical development – accelerated by the pandemic – has raised concerns about micromobility being a truly sustainable solution, seamlessly integrated into public transport, socially and economically inclusive, and aligned with the EU’s economic interests.

Nearly all of these vehicles today are provided by Asian manufacturers (China alone accounts for more than 60.000 e-bikes manufacturing companies). This means that we are currently “using” micromobility but not benefiting from the associated value-chain: the EU is missing out on a substantial economic opportunity with the potential to create up to 1Mn jobs by 2030. In addition, the products (including the batteries) we import are not sustainable and we run the risk of piling up these short-lived vehicles in our cities without the promised climate gains.

With the right incentives, this can change, and Europe can capture a sizeable share of this economy. As a matter of fact, the competitiveness of these vehicles comes down to their total cost of ownership, which can be reduced in the case of high-quality, locally built, and fully sustainable vehicles, as they are more durable than the products currently on the market.

The European battery industry, prompted by the European Battery Alliance, has adopted a similar approach with very successful results in attracting investment and reshoring the value-chain. In addition, the majority of use cases for micromobility are not yet covered, especially in the B2B segment, and the exploration of new business models is just starting, with potential around the provision of vehicles (e.g. models of asset ownership), the operation of fleets (e.g. recharging, relocation, maintenance) and other related services.

Micromobility “Made in Europe” is well-positioned, especially when considering the dynamic innovation ecosystem throughout the value-chain, with companies like ONO, Kumpan, Swobbee, DUCKT, GetHenry, etc. Strong synergies could be reinforced with the automotive and battery supply-chain. For instance, the demand from manufacturing in micromobility could require the production of about 2.5 battery Gigafactories.

Europe could start with the low-hanging fruit of last-mile logistics, sustained by a long-term trend of rising demand for delivery services, a sector especially interested in purchasing purpose-built vehicles with a longer lifespan (improving both sustainability and profitability). Scoobic, a Sevillan start-up manufacturing electric three-wheelers, can be cited as an example. Earlier this year, it entered a contract with Correos, the national postal service, to tackle emissions associated with freight transport.

Accelerating the Uptake of Micromobility with the Support of the European Union

Cities (and a few pioneering customers) have so far been in the driving seat to structure and accelerate the deployment of micromobility solutions. However critical, the support of local authorities will not be enough to ensure the emergence of a strong European value-chain and the associated benefits in terms of revenues and jobs, thus the European Union should step up.

First, financial support from European instruments is needed to accelerate and de-risk projects, and the available funds should be streamlined towards the most impactful solutions.

The Future Mobility Facility of the European Investment Bank should be spot on in that regard and will provide the necessary support for European companies (especially in the manufacturing segment) to successfully scale-up.

For smaller or less mature projects however, for instance in the “downstream” part of the value-chain, which could represent up to 75% of the value created, a better understanding of the value proposition of micromobility seems needed, starting with the EIC Accelerator which should prioritise this high-potential area in its future work. Additionally, Member States should be encouraged to use the Recovery and Resilience Facility to deploy micromobility at a larger scale.

Then, micromobility should become an integral part of the European regulatory framework for transport, and be recognised as a serious alternative to cars and vans in cities. This entails an acknowledgement of the contribution of micromobility in our climate targets and a better alignment of the current deployment with the objectives of the Green Deal.

The Fit-for-55 Package provides a most welcome boost to electric mobility but does not foresee much in terms of modal shift. Explicitly including micromobility in the target for the decarbonisation of transport in the Renewable Energy Directive and in the roll-out of recharging infrastructure in the Alternative Fuel Infrastructure Regulation would constitute a first step in this direction.

What’s more, the pending Urban Mobility Strategy offers a perfect opportunity to assert the role of micromobility and encourage its growth from the current 0.1% of trips in cities to between 10% and 15% by 2030.

Finally, the adoption of more stringent sustainability criteria for products should boost micromobility “Made in Europe”. This could be achieved through regulation, as the inclusion of light electric vehicles in the scope of the Battery Regulation proposed by the European Parliament would achieve for batteries, but also through supporting cities and public entities in reinforcing the focus on sustainability and inclusiveness when procuring micromobility solutions.

This enhanced support should contribute to the emergence of a European value-chain in the coming years, unlocking up to 1Mn jobs, and adding a further 30MtCO2eq to our decarbonisation effort by 2030.

EIT InnoEnergy has invested about 20Mn€ since 2018 in high-impact decarbonised solutions for mobility, as part of 560Mn€ invested since 2010 in sustainable energy innovation. EIT InnoEnergy is supported by the European Institute of Innovation and Technology (EIT).

______________________________________________________________________________________

1 European Environment Agency “Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Transport in Europe” (2021)

2 The km-travelled for people and for goods is expected to triple by 2050.

3 McKinsey Center for Future Mobility “Why the Automotive Future Is Electric” (2021) This fair contribution would be a reduction of GHG emissions from transport by 55% by 2030.

4 EIT InnoEnergy “Examining the Impact of a Sustainable Electric Micromobility Approach in Europe” (2021)