Can Europe strengthen its energy security while advancing decarbonization and competitiveness?

Q: From an oil & gas perspective, has Europe actually made progress on security of supply since 2022?

A: In February 2022, Europe was in a critical gas supply situation, with just under half of its gas supply lost or under threat. This is probably the most serious energy crisis since the 1973 oil shock.

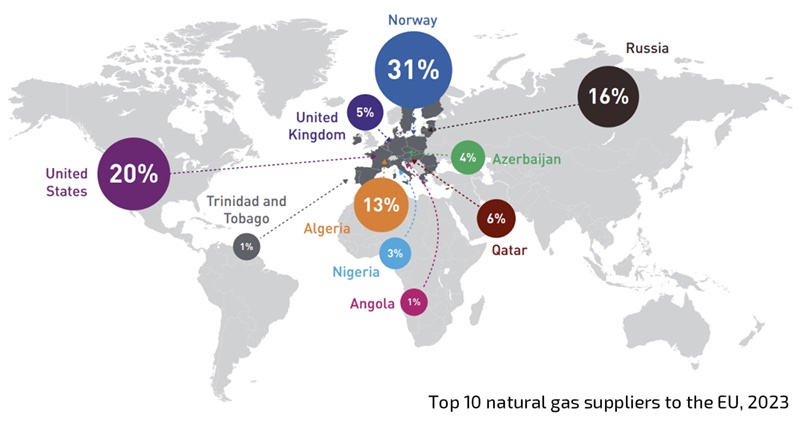

Since then, Europe’s energy security has improved in some ways but remains fragile. The EU has successfully reduced Russian gas imports from 45% of total supply in 2021 to around 15% in 2024, an incredible achievement delivered by the gas industry.

Europe weathered the storm thanks to increased reliance on LNG terminals and imports, as well as – unfortunately – significant industrial demand destruction. In doing so, it increased its exposure to spot-based supplies which are, by definition, more exposed to volatility.

Before 2022, the global LNG market was the main source of flexibility. With Russian supplies out of the picture, Europe and Asia -the only 2 continents consuming more gas than they produce- now compete directly for this market, which is expected to remain tight until 2027 when a new wave of global LNG export plants comes on stream. In the meantime, any significant energy supply disruption such as lower wind in the winter, technical issues in nuclear power generation, less hydropower in Brazil, or simply heightened geopolitical tensions and LNG trade uncertainty can create significant volatility.

Without a clear strategy supporting the signature of long-term LNG contracts and promoting domestic oil and gas exploration and production, Europe’s energy system will remain fragile and exposed to volatility.

The good news is that on both issues, the EU can do something about it if the political will is there.

Q: The EU’s regulatory landscape is evolving rapidly, but is it actually helping or hindering energy security?

A: Regulatory uncertainty is something Europe cannot afford right now. To put it simply, there are regulatory deterrents in place today in Europe which aggravate the energy security situation. These are remnants of an overzealous interpretation and application of ESG and climate considerations to policy, to which policymakers are slowly but finally waking up to.

Let me give you a couple of examples:

The EU Methane Regulation, whose concept the oil & gas industry supported from the beginning, ended up imposing prescriptive, disproportionate and unworkable operational and reporting requirements.

This created such compliance challenges for European buyers of natural gas that they now hesitate to sign long-term contracts due to potentially high penalties: this explains in part why European buyers have signed three to four times less long-term LNG supply agreements than their Asian counterparts (around 30 vs. around 120) over the past two years. To top it off, it discourages Europe’s own oil and gas producers by fear of penalties.

This regulation is a textbook case of a policy meant to push an industry to improve its processes, but which has been hijacked along the way and used against industry without assessing the impact on Europe’s security of supply. We call on the Commission to reopen the Regulation through an Omnibus proposal and tackle the problematic provisions.

Sustainability Reporting is another concern. Legislation such as the Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive include unrealistic requirements which have led essential suppliers like Qatar to publicly declare it would prefer to stop selling gas to the EU than face penalties calculated on the basis of their global turnover.

If Europe wants to ensure energy security, it must carry out a fitness check of its regulatory framework. The good news is that it’s fully within its power to do so.

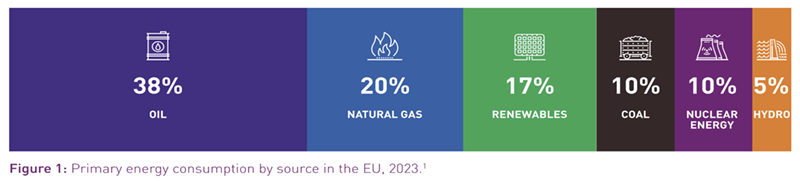

Primary energy consumption by source in the EU, 2023

Q: Is Europe too idealistic in its energy transition plans?

A: The climate neutrality objective isn’t the issue. But Europe represents around 6% of global emissions and must figure out a way to get there without destroying its industrial base. Assumptions underpinning current policies underestimate the long-term role of natural gas in the primary energy mix and overestimate the ability to deploy alternative energies.

The ‘electrification’ mantra is alive and kicking in Brussels, despite massive costs incurred by grid expansion and stabilization due to increasingly decentralized and intermittent power generation.

The approach of the past 10-15 years has shown its economic and technical limitations. Supply-side flexibility sources such as gas-fired power plants will be increasingly important, as recently shown by lower wind power generation during a cold winter.

Europe’s gas demand seems to have reached a floor after a drop of over 20% since 2022 – largely driven by lower industrial activity and not ‘colder showers at home’ as some public servants declared. We can either work to secure more gas supplies, or shut down factories and freeze in the winter. Which do we choose?

We need a pragmatic approach that supports decarbonization while maintaining flexibility in energy sourcing. Otherwise businesses will relocate to regions with more stable, or less-climate conscious energy policies.

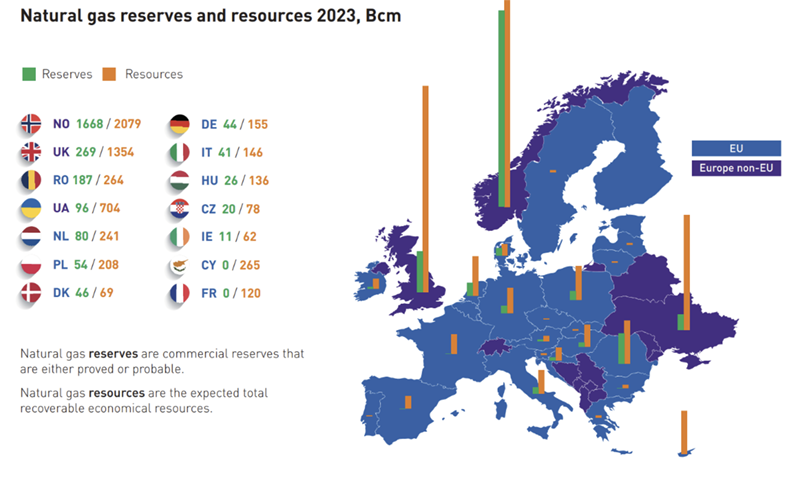

Natural gas reserves and resources, 2023 (Bcm)

Q: European oil and gas production has declined drastically. Should we reconsider domestic production to strengthen energy security?

A: Absolutely. After 15 years of renewables push, oil and gas still account for around 60% of the EU’s energy mix. But the EU has seen a 73% decline in domestic natural gas production and a 43% drop in crude oil output since 2010. While Norway remains a key producer, the EU itself only produced about 42 Bcm of natural gas in 2024 – just 13% of demand. Encouraging production in regions such as the Black Sea and Eastern Mediterranean would provide a strategic buffer to face supply volatility.

This doesn’t mean reversing climate commitments at all. The Draghi report itself recommends reassessing domestic supply to counterbalance reliance on global markets. The Commission can encourage Member States to lift remaining exploration and production bans, issue exploration licenses, adapt taxation rates, accelerate administrative processes, just like it’s doing for other technologies.

Q: EU policymakers have introduced various market interventions in response to energy crises. Are these measures solving problems or creating new ones?

A: Emergency measures are necessary when facing a crisis. But turning them into permanent features jeopardizes market functioning and creates distortions that can aggravate a tight situation. Take the Gas Market Correction Mechanism—price caps might seem like a way to protect consumers, but they also risk driving away suppliers and creating artificial shortages. Similarly, joint purchasing of gas, while well-intentioned, has had negligible impact on supply.

The EU’s energy market has functioned well when driven by competition and price signals. Emergency measures should remain temporary and targeted, rather than becoming structural barriers to a well-functioning market.

Q: What are the most urgent actions EU policymakers should take right now?

A: Policymakers should focus on five key areas:

1. Regulatory clarity and stability – Make sure legislation supports investments, not discourage it, and adjust when needed.

2. Diversification beyond short-term fixes – Send clear demand signals, strengthen partnerships with stable suppliers, invest in a broader mix of energy sources, promote domestic oil and gas production.

3. Infrastructure resilience – Accelerate LNG, pipeline, and hydrogen-ready infrastructure projects while enhancing security of infrastructures and cyber security.

4. Pragmatic pathways – Support realistic pathways that recognize the role of gas while advancing low-carbon solutions. 100% electrification is neither realistic, feasible, or affordable without making tough and unpopular choices.

5. Market-based solutions – Avoid over-regulation that could reduce competitiveness and deter long-term investments. Make no mistake: it’s mainly the market, not regulation, that got us out of the 2022-2023 crisis.

Q: If you had to give one urgent message to EU policymakers, what would it be?

A: Energy security and economic competitiveness must go hand in hand. The EU cannot afford to jeopardize its industrial base with unrealistic and unbalanced energy policies, focusing on sustainability only. We need a balanced, pragmatic approach that recognizes the continued role of natural gas, strengthens diversification efforts, and ensures a regulatory framework that fosters domestic investment rather than deters it.

The time for clear, decisive, and forward-thinking policy is now. Europe has all the potential to lead in energy innovation and compete in the global race, but only if we create a stable, investment-friendly environment that gives equal consideration to resilience, competitiveness and sustainability.