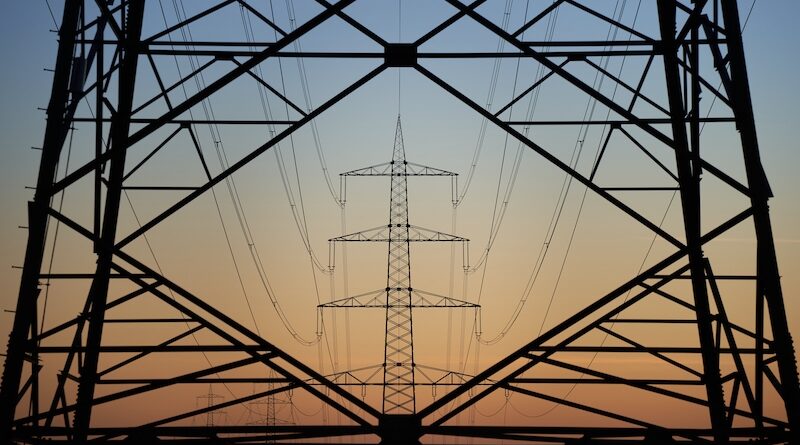

Electricity grids – enabler of the energy transition

Electricity grids are the veins of our electricity system. Without them functioning properly our electricity system will collapse. Back in the days, our electricity system was marked by big power plants —mainly gas or coal—that transported electricity via transmission lines to substations, where it was then distributed to consumers via distribution grids. However, this has changed. Electricity is increasingly generated by renewable sources. Renewable electricity is cheaper than fossil-based electricity and makes Europe independent from imports. However, this renewable electricity needs to be fed into the grid. Forecasts expect that by 2030, 70% of renewable and decentralised energy generation will be injected into the distribution grid. On the other hand, the way we consume energy changes. Heat pumps, electric vehicles or industrial electrification will increase the electricity consumption. In addition, the sun doesn’t always shine and the wind doesn’t always blow, so the generation of renewables won’t necessarily happen when the electricity is needed. Therefore, we see massive changes that the European transmission and distribution grids will need to respond to.

40 % of the European distribution grids is over 40 years old, and need to be updated. The transmission capacity across borders must also be increased. The more integrated European electricity markets are, the cheaper the energy bill for consumers.

Hence, if the grid won’t be updated and extended, it will be expensive for customers and renewable energy will be wasted – a lose-lose situation. In other words, urgent grid investments are essential to decarbonise the European power system.

The European Parliament’s own initiative report is looking exactly into these challenges: what is needed to modernise our electricity grid: Firstly, the planning of the European cross-border electricity lines needs to be improved. The underlying legislative framework needs to be strengthened. There is still too much of a national focus rather than improving the cross border angle. A stronger involvement of the European energy regulator – ACER – will bring the European focus to grid planning. Furthermore, distribution grids shall play a bigger role in the relevant planning framework and shall also be able to achieve the so-called PCI status (Project of Common Interest).

Secondly, there is the issue of financing.

Estimates say that around 584 billion EUR investments into grids are needed by 2030. This is why public EU funding like through the Connecting Europe Facility (CEF) must be guaranteed and increased, nationally managed EU funds like the Cohesion Fund or the Recovery and Resilience Facility must ensure that the Member States make sure that these funds are also used for grid enhancement and build-out and private investments should be increased, by limiting the investment risks.

Thirdly, digital and innovative technologies must be considered as alternatives to grid expansion. The deployment of so-called grid enhancing technologies should be incentivised, as they often are a cheaper and faster alternative to building new lines. Making use of digital tools and data sharing can enable flexibility through local flexibility markets. Flexible connection agreements can already be implemented now, and can contribute to increasing the grid’s efficiency.

Lastly, speaking about grid investments crossing borders, it needs to be clear who benefits and who pays the bill. This concerns countries like Austria being a transit country or Denmark with huge offshore generation. Costsharing mechanisms do currently not properly reflect the costs and benefits for Member States.

Fortunately, the European Commission has acknowledged some of the problems addressed in the report and announced certain measures, such as the Grids Package foreseen for the beginning of 2026. Only an integrated energy system will help keeping energy bills low. Therefore, it is my commitment to help getting closer to the completion of the energy union.