Resilient immunisation systems: looking beyond high vaccination rates

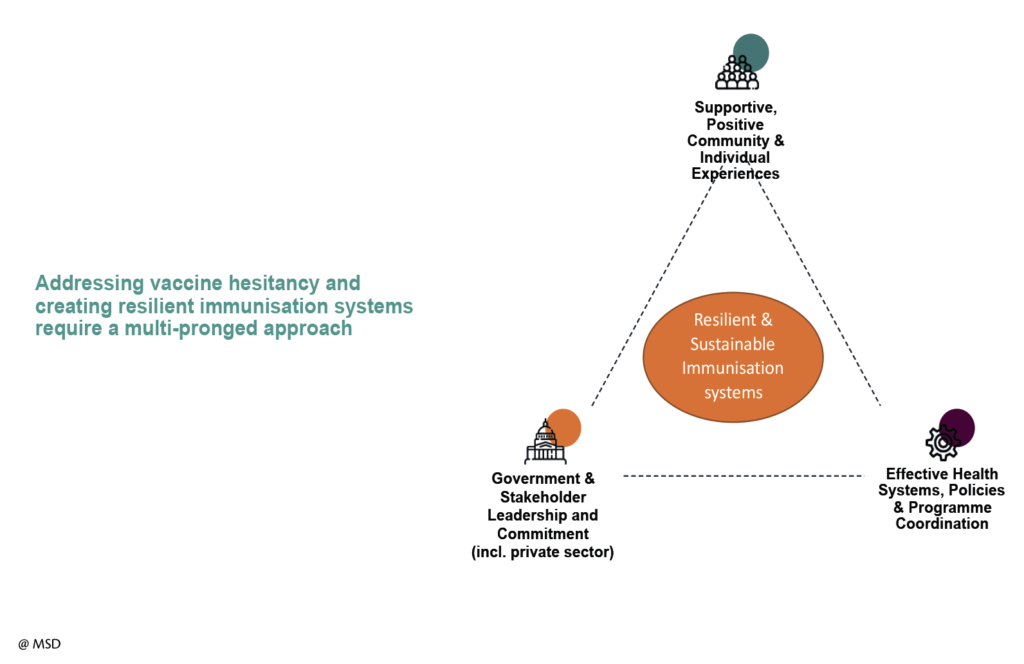

As national health budgets are under continuous pressure, the importance of successful immunisation systems becomes critical. However, we need to look beyond just achieving high vaccination rates and ensure resilient and sustainable immunisation systems are established which positively contribute to public health long term. So, where does one begin?

Responding to hesitancy

Vaccines are one of the most cost-effective and successful public health interventions available. They help prevent diseases, save lives, and improve social and economic well-being across the globe1. However, vaccine hesitancy threatens the global progress we have made in combatting the spread of many serious and preventable infectious diseases.

For this reason, it is now becoming more important than ever that we protect the hard-fought immunisation gains, and ensure they are sustained. We have to work towards delivering high-quality vaccination services through resilient systems, which are well resourced, delivered through the life-course of citizens and which are integrated into the wider national health system.

A few months ago, the World Health Organisation (WHO) identified vaccine hesitancy among the top 10 global health threats for 2019, alongside other major health challenges, such as climate change, non-communicable diseases, antimicrobial resistance and Ebola2. In September, the European Commission in collaboration with the WHO, organised a Global Vaccination Summit.

A major focus there was how we can rebuild trust in vaccination, which is a key factor in addressing hesitancy. The Summit ended with the adoption of an Action Plan3, which, unfortunately leaves a lot to be desired in terms of concrete follow up, measurable goals and operational clarity.

Undoubtedly, there is political will to fight vaccine hesitancy, but we also need political leadership and alignment across the multi-sector stakeholders involved in the development, implementation and delivery of a successful immunisation programme.

In addressing vaccine hesitancy, we all have our part to play. Our role as the innovative pharmaceutical industry is to research, develop, manufacture and distribute vaccines to address some of the most challenging public health concerns; infectious diseases which have the potential to put the health of all citizens at risk. Some of those most at risk include high risk and immunocompromised populations.

These are the populations which rely on the community immunity achieved through large population immunization. But inventing and developing vaccines is complex, time-sensitive, and carries no guarantees. It requires an ability to produce hundreds of millions of doses of high-quality vaccines and ensure the same quality in every single dose, every single time.

As we develop new vaccines, we think years ahead to anticipate and lessen hesitancy: Beyond conducting clinical trials to improve safety and efficacy, we are considering the type of information people need to promote confidence and reduce hesitancy when these vaccines become available.

In addition, we keep investing to meet the demands of new or expanded immunisation programmes around the world, which in turn, leads to an increased global demand for vaccines. Through the sharing of our scientific work we continue to contribute to the growing body of evidence related to the safety of vaccines. Nothing is more important to us than the safety of our medicines and vaccines.

Vaccine hesitancy is creating a number of concerns for those of us who are committed to addressing public health issues. One of these concerns is the effect hesitancy has on adherence. By adherence to immunisation programmes we mean access to vaccination in due time, based on national recommendations. Ensuring the full course of the vaccination programme is delivered is critical to benefit from the full potential of vaccination. Take, for instance, the example of measles, which requires two doses.

Adhering to the programme schedule and administering both doses is critical to ensure the vaccine’s immunity protection. To solve the problem, we need immunisation systems that have strong infrastructure for adequate surveillance and monitoring, we also need to run public awareness campaigns, provide adequate training to healthcare professionals, and improve access. If all of this is achieved it will contribute greatly to the resilience of the programme, build public and professional confidence and increase uptake.

Creating a resilient immunisation programme

In addition to the issue of hesitancy, a major barrier to sustained high vaccination coverage and trust in immunisation programmes lies in the inability of our healthcare systems to properly prepare for and respond to crises. An example of this is the recent measles outbreaks in Europe.

This crisis has focused attention on the need to start looking beyond just increasing vaccination coverage rates, and towards taking a more comprehensive approach by building resilient immunisation systems.

A resilient system is able to recover or “bounce back from adversity” following the experience of negative events, threats or hazards4. At its core, this concept of resilience is rooted in planning for the successful sustainability of the programme but also a quick recovery in the face of a challenge. Resilience is a state where an issue does not have an opportunity to take hold. It is where an issue or threat can be isolated quickly, dealt with and managed without it affecting the immunisation programme or other parts of the health system.

Recent research56 suggests that you can characterise a resilient immunisation system as:

a. Aware and therefore able to identify emerging risks, system weaknesses and strengths and is in a position to map out strategies for engaging strengths and reducing weaknesses.

b. Integrated and thus ensuring recognition and coordination between key system sectors.

c. Adaptive, indicating an ability to change to better position itself to succeed in warding off crises, or mitigating threats, when they do occur.

d. Capable, implying the possession of a broad range of skills, assets and resources to meet its needs.

e. Self-regulating and thus able to quickly isolate threats and minimise threats to essential services.

Building resilient immunisation systems is key to sustaining high vaccine uptake and helping communities prevent, manage and recover from hesitancy-related issues. Finding better ways to anticipate and prevent such issues will protect both individual and public health. The worrying rise in vaccine hesitancy is threatening to reverse the remarkable decades-long gains made by vaccines. Therefore, building and sustaining resilience in immunisation programmes is now critical.

Take, for example, the case of France, which in January of 2018 introduced mandatory vaccination in an effort to address the worrying drop in vaccine coverage rates. They identified the issue and took action to address it demonstrating bold leadership to safeguard public health. However, the bigger question is why trust in vaccination and the immunisation system had dropped so low that this measure was required.

The need to work together

Over the past few decades immunisation programmes have expanded as a result of the introduction of innovative new vaccines and new evidence which demonstrate the benefits to wider populations. However, this creates significant complexity in the system. The complexity is mirrored in the variety and numbers of actors involved: from individual and community groups, to healthcare professionals, advisory bodies, public health institutes and policy makers to name just a few. In addition, other “non-traditional” actors and platforms which share information on vaccination, such as social media platforms and religious leaders further add to the complexity.

Acting together, each component of this vaccine ecosystem has the potential to collaborate and strengthen the resilience of the immunisation system.

Understanding how to build a resilient and sustainable system by engaging all stakeholders, respecting their interrelationships and what roles they play in an immunisation programme may therefore be key to promoting the resilience of successful immunisation programmes.

It is time for the EU institutions and Member States to start investigating how to build and sustain resilient immunisation systems by firstly assessing the vulnerabilities and strengths within member states.

Ensuring resilience assessment indicators are developed and used in a harmonised way across the European region is a good place to start. This should be central to the work already started under the EU Vaccination Roadmap going forward.

1 – https://www.who.int/immunization/sage/meetings/2014/october/SAGE_working_group_revised_report_vaccine_hesitancy.pdf?ua=1

2 – https://www.who.int/emergencies/ten-threats-to-global-health-in-2019

3 – https://ec.europa.eu/health/sites/health/files/vaccination/docs/10actions_en.pdf

4 – WHO-EURO. Building resilience: a key pillar of Health 2020 and the Sustainable Development Goals Examples from the WHO Small Countries Initiative. 2017. http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0020/341075/resilience-report-050617-h1550-print.pdf?ua=1

5 – Kruk ME, Ling EJ, Bitton A, et al. Building resilient health systems: a proposal for a resilience index. BMJ (Clinical research ed) 2017; 357: j2323.

6 – Kruk ME, Myers M, Varpilah ST, Dahn BT. What is a resilient health system? Lessons from Ebola. Lancet (London, England) 2015; 385(9980): 1910-2.